Clouds ascend like sculptures, backlit by the setting sun. Wispy pink columns stand in dramatic array, the clump on top of one stack embellished with a viciously straight contrail that angles upward like a laser beaming from a cyclopean eye. It is a tiny thing but still audacious enough to pitch a galactic battle against an unseen enemy. The day closes over the Mississippi, with stormheads threatening their bounty of rain from the south. Colin and I have left the gentle wash of music and companionship of old friends on Mud Island, a sanctuary of gentile life only a stone’s throw from the urban grittiness that awaits patiently on the east shore of the mighty river.

Impossibilities Aggregate

We are not supposed to be here. Colin was never to return to Memphis, this place of salvation that sheltered us and drew us out of despair nearly seven years ago. Recently, he asked to come back for a visit with no medical appointments, just to see friends. I responded with a patronizing smile. That would be nice but not in the cards, the unspoken words evincing the constraints of my world view.

In Ithaca, we were settling into the rhythm of homeboundness that comes with palliative care. Especially after our rigorous travel itinerary, Colin wanted only to stay home and be with his family. His appetite for going to school waned steadily, despite our encouragement and efforts to make the experience there as positive as possible. We could feel the walls closing in, gently padded but firm. Yet again, we sensed the edge of the precipice pressing insistently into our feet.

Clinically, Colin wasn’t much different. He would periodically experience headaches and sometimes accompanying vomiting, but all of this was sporadic and possibly remedied by a few pumps on the valve of his shunt. The valve refilled sluggishly, but it refilled. A look at any of the scans since November would inform one that the shunt was earning its keep; there was no way he could tolerate the presence of such a prolific disease without periodic flushing of CSF through the shunt.

The shunt is a differential pressure valve, a simple mechanism that operates when the pressure on one side exceeds the pressure on the other by a certain amount. The shunt can fail because of detritus clogging the valve or occlusion of either end. Its response is also affected by the distal end, the gut, and conditions that increase pressure there can delay the emptying of CSF into the peritoneum. It is possible for the tubing to become kinked, temporarily or permanently.

It is easy to explain away a problem that is sporadic and quickly resolves, and Colin was on active treatment that could plausibly be keeping the disease at bay. The last we knew, from the February scan, progression had halted. Under the circumstances, with such few symptoms, progression would likely be modest. It was easy to believe this, at any rate.

The breathing room that everolimus created, whether real or imagined, also gave me the opportunity to start assiduously researching options. Managing the medical aspect of Colin’s care can be exhausting, especially when balanced against the necessity of attending to end-of-life issues. However, we were able to attend to these concerns before Christmas and throw ourselves into the half-desperate effort to have a good time. Dammit.

For various reasons, we moved up Colin’s follow-up scan from the end of May to the sixth. The initial rationale was to get a clear picture before we would need to renew the everolimus prescription. More tactically, we also knew that it was important to know—to KNOW—what was going on because we now had other options. The only very apparent change we had seen in Colin was emotional. In the week before the scan, he had become extremely clingy and dependent, absolutely refusing to go to school. I often worked on my laptop next to him, my presence alone comforting but necessary. He would not admit to any physical change, but he said he was scared. Once comforted, he was blissfully happy, perfectly content to watch a Disney movie with me next to him, even if I was tapping away on my computer or asleep with my arms wrapped around him.

Clarity Begets Action

Medical decision making is constructed around one basic idea: if you gain information, will it change treatment? If you asked me this question in March, I would have said no. By May, it was potentially yes. The longer we waited, the worse the situation and the more likely that answer would turn into no.

On May 6, Colin went to Rochester for his second unsedated MRI. Our arrangement was to meet with an oncologist to get preliminary results so we would have some idea of what to do. We didn’t get a very detailed read of the scan, but it was clear that Colin had progressed. The frontal lesion had gotten bigger and more problematic, creating significant edema, shifting the brain off the midline. The distortion of the corpus collosum is obvious. I could not see any free CSF in the ventricles, which appeared utterly congested with tumor.

There were some issues with the scan that I still haven’t gotten to the bottom of; it was impossible to pull up side-by-side comparisons of the two sets of scans done in Rochester. For this reason, we saw only small pictures. It felt mercifully like looking through a telescope backwards. I walked away with the impression that it wasn’t clear how the shunt could be working, and it wasn’t at all clear how my son could be alive in the first place.

Days later, after I had uploaded the scan to the Johns Hopkins database and I had done the same within Google Drive and started sending off the images, I finally started looking at the pictures myself. MRI interpretation is not a strong suit, but I came away with the same basic impression. However, I had in front of me a child who was very much alive and happy.

The fateful scan, on a Monday, precipitated three conversations with pediatric neurosurgeons on that Friday. We are extremely fortunate to be able to garner such capable and motivated resources in that period of time. Before going to bed on Friday, we had determined to return to Memphis for Colin’s sixth resection, his fourth with Dr. Boop. In my conversation with Dr. Boop, he gave a very good and terrifying consult. We could go in and cause more problems than we fix. The tumor could have become so aggressive that it would return quickly. It could have become so vascular and invasive that he could bleed out on the table. If you let things take their course, he will likely get sleepy and eventually pass gently, naturally.

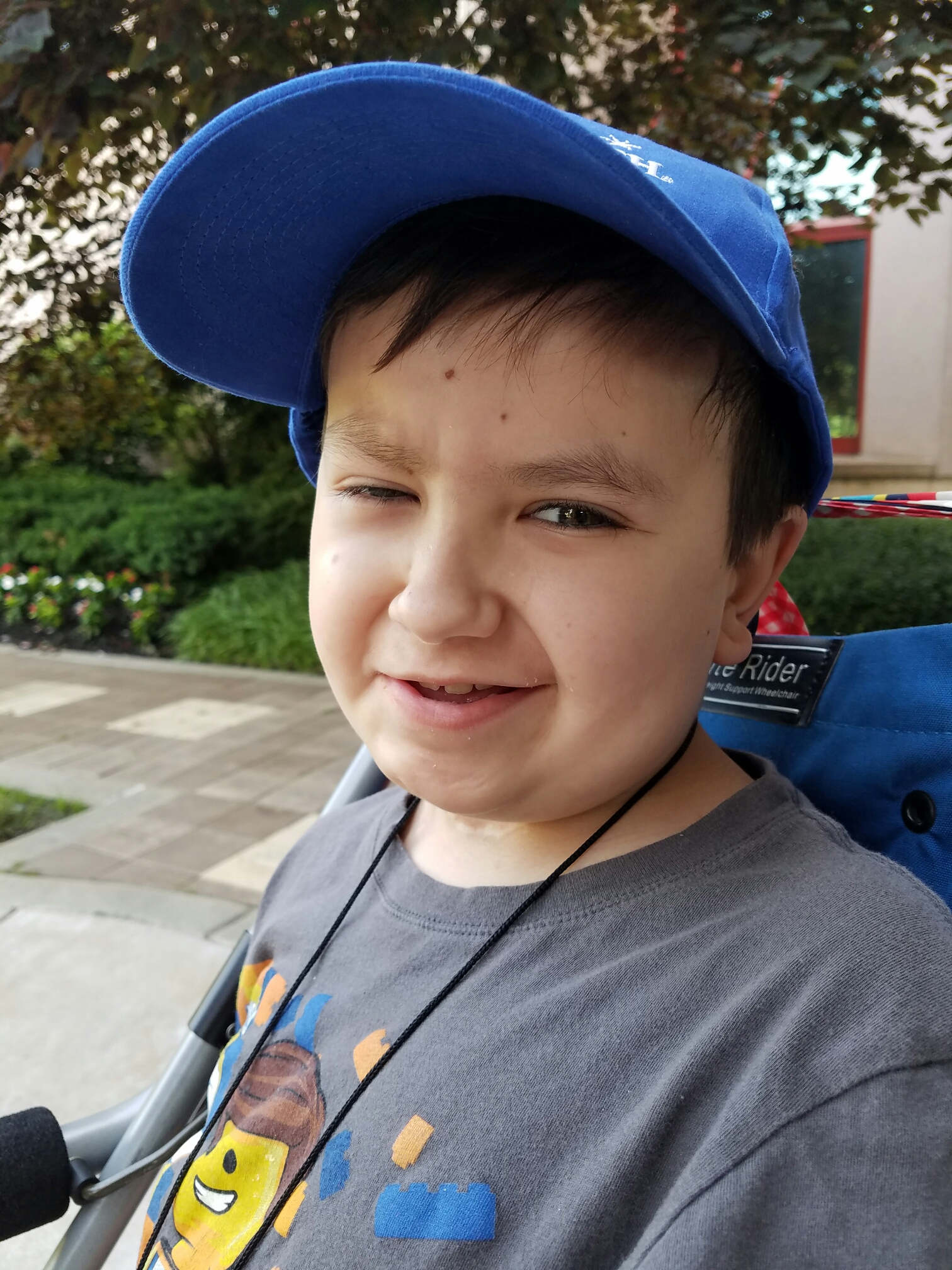

We have been very determined to avoid a medicalized death for Colin. We want peace and gentleness for him when the time comes, the same we would wish for anybody. Along with the scans, I also sent a picture of Colin, very much alive and happy with his new kittens. This was what we were fighting for, not an MRI. In many ways, Colin showed us that he could be content with very little, and that knowledge has encouraged us to push the envelope to extend his life.

Nine days after an MRI that told me that my son had no reason to be alive, he was under the knife, in the ever-capable hands of Dr. Boop. He is not a magician; he knows that his services are necessary but not limitless. However, there is no person better equipped for this job, and most would not even attempt it in the first place. He judged that it could derive more benefit than harm but that it could cause harm that we needed to confront before deciding.

Neurosurgery Rockstars

After the appropriate cautions about complications and side effects, Colin emerged from surgery quickly, with minimal blood loss, and mission accomplished. Dr. Boop was able to remove the frontal lesion that extended along the length of the previous surgical tract, drained two large cysts, and assured that CSF flow was clear. Colin was out of surgery quickly and spent one night in the ICU, then another on the floor.

We were concerned about his memory and overall sluggishness, so we nearly stayed another night. When the physical and occupational therapists came and I mentioned that he was sluggish, he looked at them and responded, “I’m sloooooooow.” Knowing that his sense of humor was intact, we soon after lobbied to get out of the hospital. He was tired and his memory was a little shot (he couldn’t remember how we’d gotten to Memphis), but it was worth securing his liberation.

As a post-surgical strategy, we knew we wanted to pursue some kind of radiation and conduct tumor testing to see if he could be treated with Herceptin, the breast cancer monoclonal antibody that targets HER2, which is commonly found in recurrent ependymoma. In our consult with Dr. Merchant, he suggested craniospinal irradiation (CSI), which was absurdly aggressive and inappropriate for a palliative case. I lobbied for a different option and we met again.

In the meantime, a pediatric neurooncologist who is notoriously against radiation strongly recommended CSI. We also realized that Colin has shown us his capacity for happiness while functioning at a relatively low level. After surgery, when I asked him how he was feeling, he responded, “Happy, and happy to be alive.”

In fewer than nine years, Colin has mastered what others often fail to capture in the course of many more decades. He is happy to be alive. He relishes the love and companionship of his family and friends. He needs little and cannot tell you what he wants for his birthday. He wants to be happy, and there is no particular physical gift that gets him across the finish line.

Full-bore CSI is the best option to extend Colin’s life. Though this was pointedly not our goal last year, he has shown us that he has the tolerance and the inclination to do this. The little boy who not long ago resisted taking a pill every day has also had the opportunity to regroup and let us know that he is willing to lose much as long as he does not lose the concrete reminders that he is loved.

We have strategies to squeeze more juice from the orange and will do so if it makes sense for Colin. Our definitions of quality of life have changed based on what he has shown us, but they are utterly malleable. If there is any lesson we have learned in these last seven years, it is that we must deal with what is in front of us, not decisions that were made in the past. We have facts, not preconceptions. We have evidence, not emotional attachment. These tools are the machete that clear the path that we walk on Colin’s behalf.

Storms, Ever Approaching

The weather in Memphis has been unpredictable and harsh. Storms move in like typhoons, winds shaking trees and buckets of rain darkening the pink walls of the hospital. When the clouds part, the sun dries the ground and mocks the forbidding sheets of water that once demobilized us. However, the drops return, threatening to expand beyond an innocuous sprinkling that scatters dark spots on our clothes.

To the south, I see luscious stacks of whiteness, voluptuous puffs of water vapor rising into the air, their texture elucidated in the sharp light of the low-lying sun. Among a tableau of pre-Colin photographs, we have a family picture with Aidan as a chubby-cheeked but serious looking toddler, a snapshot from a trip to the Caribbean. Several similar clouds lurk benignly in the background. One of these evolved into Hurricane Katrina, which famously unleashed its destructive force on an ill prepared New Orleans.

I see the clouds and I know they are coming, but it is impossible to discern perspective and how long it will take for them to arrive. The rain comes with relentless fervor but irregular timing, and I count on this ambiguity to embrace the eternity of each moment. When I hold Colin, he is palpably alive: warm and breathing, a strong and regular pulse propelling one moment to the next. There is no reality other than this.

Love to you all. Thank you so dearly for these updates. Colin you are incredible!

With all the research and hope that you provide, Colin is in good hands. Glad to hear surgery went well. Hope you all can rest and that Colin can do some normal boy things. I think and pray for you all often. I just had a stable scan with the reduction of Avastin, so they are reducing it again. Still having terrible joint pain that keeps me awake even on pain medicine. I am still very functional and lucky to be so. I shouldn’t be complaining. Take care and I will continue to pray for you all. Anne Murray

I am always awed by your beautiful and poignant expressions. Colin has proven over and over he is one special kid! I have heard that butterflies can fly after losing more than 75% of their wings; that’s Colin. Still flying and enjoying it! It is wonderful that you and Ian are sensitive to his leadings and so gracefully change and adapt to his needs. You make it look natural and easy, but like an athlete doing a difficult routine, I know it takes courage and strength.

You are in my prayers ….

Love, Diana

My heart was touched yesterday when I met you and Colin at the Botanic Garden. Thank you for sharing your amazing story. Please tell Colin that the lady who gave him the green frog/pencil sharpener hopes he is having a good day. I hope we will meet again.

Our hearts are with you, Colin, Aidan & Ian. You are such a strong family unit. You’re such amazing parents. We hold you all in our prayers continuously. I know our last camp sunshine session things were not looking too good but I am so happy to hear this surgery went well. He looks so happy with his kitten. Thank you so much for sharing with us. God Bless you all! You are love immensely! ❤️🙏

Hi you guys. I have been quietly following your story on FB and I just wanted to let you know that I think you are doing the right things all along. My thoughts are with you on your long journey and you are truly blessed to have each other and to make the best of every day.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful family’s journey and for reminding me to breathe in each day’s beauty and our own realities. I am learning so much from your courageous nine year old boy that it shames and humbles me. Thank you. Rosemarie